|

| Josef Sudek |

From Josef Sudek by Charles Sawyer [Originally published in "Creative Camera", April 1980, Number 190]

Prologue:

Josef Sudek was born in 1896 in Kolin on the Labe in Bohemia. As a boy he learned the trade of bookbinding. He was drafted into the Hungarian Army in 1915 and served on the Italian Front until he was wounded in the right arm. Infection set in and eventually surgeons removed his arm at the shoulder. During his convalescence in an Army Hospital, he began photographing his fellow inmates. After his discharge, Sudek studied photography for two years in a school for graphic art in Prague. Between a disability pension and intermitment work as a commercial photographer, Sudek made a living. In 1933, he held his first one-man show in the Krasnajizba salon. Since 1947, he has published eight books. In the early 1950's, Sudek acquired an 1894 Kodak Panorama camera whose spring-drive sweeping lens makes a negative 10 cm x 30 cm. He employed this exotic format to make a stunning series of cityscapes of Prague, published in 1959.

Sudek's work first appeared in America in 1974 when the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, gave him a retrospective exhibition. The same year Light Gallery in New York City showed an exhibition of his photographs. On his 80th birthday in April, 1976, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague inaugurated a comprehensive retrospective exhibition of Sudek's work which later appeared at the Photographer's Gallery, London.

In spite of his disability, Sudek always used large format cameras and from the 1940's on he made only contact prints. He worked without assistants in the open air in city and countryside. His hunched figure supporting a huge wooden tripod was a familiar sight in Prague. Although he never married and was rather shy, he was not a recluse and was renowned for his weekly soirees for listening to classical music from his vast record collection. Sudek died quietly and without suffering or illness in mid-September 1976 in Prague.

Sudek, The Man And His Work:

Josef Sudek was born in 1896 in the industrial town of Kolin on the River Labe in Bohemia. Czechoslavakia then existed only in the imagination of a few visionary artists, particularly writers, and of some political activists. Emperor Franz Josef reigned on the Hapsburg throne and Bohemia was a Kingdom in the Austro- Hungarian Empire. Josef's father was a house painter and he apprenticed his son to a bookbinder; a fellow worker introduced the young man to photography. In 1915 he was drafted and assigned to a unit on the Italian front. After slightly less than a year in the line, he was wounded in the right arm. The wound was not serious, but gangrene set in; a long struggle ensued and finally Sudek's arm was removed at the shoulder. For three years, he was a patient in a veteran's hospital; it was there, during his recuperation, that he first began photographing in earnest.

The years from his leaving the veteran's hospital around 1920 until 1926 were restless years for Sudek. He could not take up his trade of bookbinding. He was offered an office job but turned it down. After settling in Prague, he cast about for a new lot. He considered taking up the life of a small merchant but had no taste for it. To keep body and soul together, he took photographs for small commissions. He joined the Amateur Photography Club and struck up a friendship with Jaromir Funke, a well-educated, vocal, young photographer with advanced aesthetic theories concerning photography. In 1922, Sudek enrolled in the School of Graphic Arts in Prague and received an old-school, formal education in photography. Two main subjects occupied his attention with his camera: his former fellow-patients, the invalids in the veteran's hospital, and the reconstruction of St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague then in progress. Occasionally he returned to his native Kolin to photograph the leisure life in the parks of the city. Still, he was unsettled, apparently not yet reconciled to his loss. And he was contentious. Together with his friend Funke, he was expelled from the Photography Club for his impatient opposition to those who stood firmly by the then entrenched techniques of painterly affectations. The two upstarts gathered other like-minded photographers and formed the avant-garde Czech Photographic Society in 1924, devoted to the integrity ot the negative and freedom from the painters' tradition. Although Funke was the same age as Sudek, he had already studied law, medicine and philosophy. Sudek admired his superior education and intellectual capacities, and their discussions often led to ambitious projects.

In 1926, Sudek suffered a life crisis brought on when he accepted an invitation from his friends in the Czech Philharmonic to join them on tour initaly. His description of the odyssey is reproduced by Bullaty (page 27). It runs as follows:

"When the musicians ot the Czech Philharmonic told me: 'Josef come with us, we are going to Italy to play music,' I told myself, 'fool that you are, you were there and you did not enjoy that beautiful country when you served as a soldier for the Emperor's Army.' And so went with them on this unusual excursion. In Milan, we had a lot of applause and acclaim and we travelled down the Italian boot untill we came to that place -- I had to disappear in the middle of the concert; in the dark I got lost, but I had to search. Far outside the city toward dawn, in the fields bathed by the morning dew, finally I found the place. But my arm wasn't there - only the poor peasant farmhouse was still standing in its place. They had bought me into it that day when I was shot in the right arm. They could never put it together again, and for years I was going from hospital to hospital, and had to give up my bookbinding trade. The Philharmonic people apparently even made the police look for me but I somehow could not get myself to return from this country. I turned up in Prague some two months later. They didn't reproach me, but from that time on, I never went anywhere, anymore and I never will. What would I be looking for when I didn't find what I wanted to find?"

From Sudek's sketchy account of his crisis in 1926, we get a picture of a restless and troubled man accepting a casual invitation that leads him near the very spot where years before his hope for a normal life had been shattered. Leaving his friends, in mid-concert he wanders somnabulent until near dawn he comes to the exact place where, nearly ten years before, his life was forever changed. Unable to abandon hope of recovering his lost arm, he stays two months in that place, cut off from his friends and his world in Prague. Finally, his mourning complete, reconciled, but permanently estranged, he returns to Prague, where he immerses himself in his art.

The interpretation of Sudek's life offered in the previous paragraph seems to me reflected in his photography and borne out in his life style. His photos from 1920 until the year of his crisis are markedly different, both in style and content, from those following. In the series from the veteran's hospital taken in the early 1920's, his former fellow-invalids are seen as ghostly silhouettes shrouded in clouds of light -- lost souls suspended in Limbo. In the photos of Sunday pleasure-seekers in his native Kolin from the same period, the people are seen from 6 distance, through soft focus, in social clusters, usually with their backs to the camera, suggesting the closure of the ordinary social world to outsiders. His extended study of the reconstruction of St. Vitus begun in 1924, two years before his crisis, and completed in 1928, with the publication of his first book, can all too easily be taken as a metaphor for his personal struggle to reconstruct his own life.

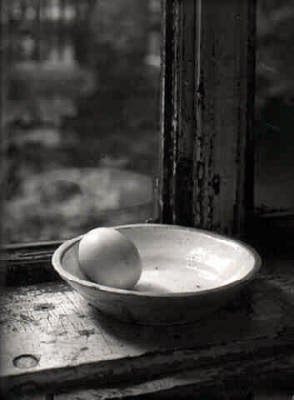

After 1926, Sudek began to find his own personal style and come into his full powers as an artist. Gone is the haze of soft focus, and gone too, are the people -- even most of his cityscapes show deserted streets. He turned his attention to the city of Prague with devotion and dedication that are rare even among the most committed artists. He succeeded to capture both the grandeur and the unpretentiousness of that lovely city. Yet, lovely as it still looks, through his lens it is empty. As if to compensate for the absence of the human factor in its customary place, Sudek personified the inanimate. The woods of Bohemia and Moravia projected on his view-screen were inhabitated by "sleeping giants", as he called them, huge dead trees that watched over the landscape like statues out of Easter Island. In his playful moods, Sudek toyed with masks and statuary heads, showing them as lovers, as grotesqueries, or even as gods. He found intimacy hard to achieve -- perhaps because it was painful -- not just in his interpersonal life but even under his viewing cloth. Its substitute came easily with inanimate objects. "I love the life of objects," he told one interviewer. "When the children go to bed, the objects come to life. I like to tell stories about the life of inanimate objects." He devoted endless hours to photographing special objects in various settings, particularly objects given to him by friends. He often called these photos "remembrances" of this or that person. It appears as if his personal rapport with the inanimate things he photographed so lovingly began as an alternative to real intimacy with other persons and evolved into a means to bridge the gap that stood between him and the others.

As he came to his artistic maturity, immersion in work and devotion to a high standard of craftsmanship became the dominant motifs of Sudek's life. In 1940, he saw a 30 x 40 cm photograph of a statue from Chartres, which, he recognized, was not an enlargement but one made by the contact process. The print so impressed him for its rendering of the stone material that he vowed thereafter always to make contact prints. He said it was less the fineness of details he craved in contact prints, than their tonal variation. From then on he lugged view cameras as large as the 30 x 40 cm format (roughly 12 x 16 inches) around the steep streets of the Hradcany and Mala Strana sections of Prague, working with one hand, cradling the camera in his lap to make adjustments, using his teeth when his hand was insufficient.

No photographer, save possibly Atget, was so devoted to the task of portraying a city, and with such stunning results, as Sudek. He couldn't have had a better subject than Prague; not even Atget was so lucky with Paris. Prague is, to many, the jewel of Europe. In the days when Europe from Paris to St. Petersburg was still one cultural continuum, Prague was considered the heart of the continent. The city was Mozart's second home after Vienna (the Czechs seemed to him to have appreciated him more than his fellow Viennese), and it also was Kafka's native city. Somehow the two blend, as do the massive buildings of the city of Gothic, Rennaissance, and Baroque architecture. (The modern buildings, especially housing estates, are mercifully placed on the outskirts of the city). Two features dominate the city: Charles Bridge, the footbridge spanning the Vltava, lined with statues depicting the history of Christianity and the Czechs, and Hradcany Castle, a sprawling fortress enclosing several courtyards, the traditional residence of Czech kings, as well as St. Vitus Cathedral. Charles Bridge dates from the 14th century and Hradcany's earliest construction dates from the 12th century. The castle, which is on the crest of a steep ridge rising from the west bank of the Vltava, dominates the profile of the city seen from the east bank of the river. In all, Sudek compiled seven books of Prague photographs. He left the streets only toward the very end, when old age added to his handicap and made moving around the city with his camera a titanic struggle. In the Prologue to her book (p. 14), Sonja Bultaty tells an anecdote about helping Sudek photograph Prague. It portrays the special relationship between him and the city.

"I remember one time, in one of the Romanesque halls, deep below the spires of the cathedral [St. Vitus] - it was dark as in catacombs - with just a small window below street level inside the massive medieval walls. We setup the tripod and camera and then sat down on the floor and talked. Suddenly Sudek was up like lightening. A ray of sun had entered the darkness and both of us were waving cloths to raise mountains of dust 'to see the light,' as Sudek said. Obviously he had known that the sun would reach here perhaps two or three times a year and he was waiting for it."

His workman-like attitude applied not only to the purely technical side of things but to the aesthetics of his camera work as well. Nowhere does this show so clearly as in his panoramic photos. The unusual format with its extreme proportions of 1 x 3 and the special distortions caused by the sweeping lens are extremely demanding, like the constraints of a sonnet. Yet like any set of artistic constraints, the peculiar requirements of the panoramic photo offer opportunities not found elsewhere. Sudek never tired of exploring the possibilities of the photographic sonnets he could make with his antique mechanism whose shutter speeds were marked simply "fast" and "slow". With it he gave us a geodesic feeling for the country-side which far surpasses anything we get from isolated views, and in Prague itself he showed how the River Vltava is an integral part of the city and how the labyrinthian quality of the city is offset by its broad open spaces. He was never short of resourceful ways of using the panoramic format. Before the horizontal panorama had yieided all its secrets, Sudek turned the camera on its side and gave us vertical panoramas!

The systematic approach, and the dogged aesthetic experimentation of Sudek are akin to the working habits of Cezanne. But these alone are insufficient to make great art or even good art. On the contrary, if these are all one sees in a work, then the cumulative burdern of so much plain labor would be unbearable. Sudek's devotion to work may have integrated his shattered life but it could not have offered him the spiritual redemption he was seeking; only his aesthetic quest could bring this. It is the struggle for spiritual redemption through his aesthectic quest that gives Sudek's best photographs their true power. Two qualities characterize his best work: a rich diversity of light values in the low end of the tonal scale, and the representation of light as a substance occupying its own space. The former, the diversity of light values, requires very delicate treatment of the materials, especially the negative, but also the paper (Sudek used silver halide papers in the main). The latter, the portrayal of light as substance, is a more original trait then his tonal palette, which one sees in occasional prints of other photographers. Flaubert once expressed an ambition to write a book which would have no subject, "a book dependent on nothing external ... held together by the strength of its style." Photographers have sometimes expressed parallel aspirations to make light itself the subject of their photographs, leaving the banal, material world behind. Both ideals are, of course, unobtainable, but nonetheless they may be worth pursuing. (Artists, in their pursuit of the unobtainable, are not so likely to be called pathological as others, of us, though recent developments in ihe philosophy of science tend to view the scientist's quest for truth as equally quixotic). Sudek has come closer than any other photographer to catching this illusive goal. His devices for this effect are simple and highly poetic: the dust he raised in a frenzy when the light was just right, a gossamer curtain draped over a chair back, the mist from a garden sprinkler, even the ambient moisture in the atmosphere when the air is near dew point. The eye is usually accustomed to seeing not light but the surfaces it defines; when light is reflected from amorphous materials, however, perception of materiality shifts to light itself. Sudek looked for such materials everywhere. And then he usually balanced the ethereal luminescence with the contra-bass of his deep shadow tonalities. The effect is enchanting, and strongly conveys the human element which is the true content of his photographs. For, throughout all his photography, there is one dominant mood, one consistent viewpoint, and one overriding philosophy. The mood is melancholy and the point of view is romanticism. And overriding all this is a philosphic detachment, an attitude he shares with Spinoza. The attitude of detachment that characterizes Sudek's art accounts for both its strength and weakness: the strength which lies in the ideal of utter tranquility and the weakness which is found in the paucity of human intimacy. Some commentators find Sudek's photos mysterious but I think this is a mistake: the air of mystery vanishes once we see in Sudek's photography a person's private salvation from despair.