|

| Lady Clementina Hawarden |

|

| "Untitled", 1861 |

|

| "Agnes and Lionel", ca. 1862 |

|

| "Clementina Maude and Florence Elizabeth", ca. 1864 |

|

| "At the Window", 1864 |

|

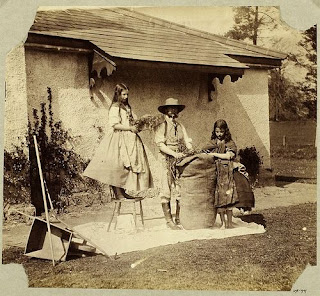

| "Agnes Elphinstone", ca.1861 |

Biography from artdaily.com:

Born Clementina Elphinstone Fleeming in Dunbartonshire in 1822, she was the third of five children of a British father, Admiral Charles Elphinstone Fleeming (1774-1840), and a Spanish mother, Catalina Paulina Alessandro (1800-1880). In 1845 she married Cornwallis Maude, an Officer in the Life Guards. In 1856 Maude's father, Viscount Hawarden, died and his title, and considerable wealth, passed to Cornwallis.

The surviving photographs suggest that Clementina, now Lady Hawarden, began to take photographs on the Hawarden's Irish estate at Dundrum, Co. Tipperary, from late 1857. Many of these were taken with a stereoscopic camera, and the present collection contains several Dundrum images which are one of the pair that comprise a stereoscopic image.

In 1859 the family also acquired a new London home at 5 Princes Gardens (much of the square survives as built, but No. 5 has gone). From 1862 onwards Lady Hawarden used the entire first floor of the property as a studio, within which she kept a few props, many of which have come to be synonymous with her work: gossamer curtains, a Mark Haworth-Booth offered Virginia Dodier the opportunity to make a freestanding mirror, a small chest of drawers and the iconic 'empire star' wallpaper, as seen in several of these photographs. The superior aspect of the studio can also go some way to account for Hawarden's sophisticated, subtle and pioneering use of natural light in her images.

It was also here that Lady Hawarden focused upon taking photographs of her eldest daughters, Isabella Grace, Clementina, and Florence Elizabeth, whom she would often dress up in costume tableau. The girls were frequently shot - often in romantic and sensual poses - in pairs, or, if alone, with a mirror or with their back to the camera. Hawarden's photographic exploration of identity, otherness, the doppelgänger and female sexuality, as expressed in the vast majority of these photographs, was incredibly progressive when considered in relation to her contemporaries, most notably Julia Margaret Cameron. As Graham Ovenden comments in Clementina Lady Hawarden (1974), "Clementina Hawarden struck out into areas and depicted moods unknown to the art photographers of her age. Her vision of languidly tranquil ladies carefully dressed and posed in a symbolist light is at opposite poles from Mrs Cameron's images...her work...constitutes a unique document within nineteenth-century photography."

She exhibited, and won silver medals, in the 1863 and 1864 exhibitions of the Photographic Society, and was admired by both Oscar Rejlander, and Lewis Carroll who acquired five images which went into the Gernsheim Collection and are now in Texas. In 1865 Lady Hawarden died, and although her loss was regretted in the photographic journals, her work was soon forgotten.

A major retrospective of Lady Hawarden's life and work can be found in Virginia Dodier's book, "Lady Hawarden: Studies from Life, 1857-1864".

Born Clementina Elphinstone Fleeming in Dunbartonshire in 1822, she was

the third of five children of a British father, Admiral Charles

Elphinstone Fleeming (1774-1840), and a Spanish mother, Catalina Paulina

Alessandro (1800-1880). In 1845 she married Cornwallis Maude, an

Officer in the Life Guards. In 1856 Maude's father, Viscount Hawarden,

died and his title, and considerable wealth, passed to Cornwallis.

The surviving photographs suggest that Clementina, now Lady Hawarden,

began to take photographs on the Hawarden's Irish estate at Dundrum, Co.

Tipperary, from late 1857. Many of these were taken with a stereoscopic

camera, and the present collection contains several Dundrum images

which are one of the pair that comprise a stereoscopic image.

In 1859 the family also acquired a new London home at 5 Princes Gardens

(much of the square survives as built, but No. 5 has gone). From 1862

onwards Lady Hawarden used the entire first floor of the property as a

studio, within which she kept a few props, many of which have come to be

synonymous with her work: gossamer curtains, a Mark Haworth-Booth

offered Virginia Dodier the opportunity to make a freestanding mirror, a

small chest of drawers and the iconic 'empire star' wallpaper, as seen

in several of these photographs. The superior aspect of the studio can

also go some way to account for Hawarden's sophisticated, subtle and

pioneering use of natural light in her images.

It was also here that Lady Hawarden focused upon taking photographs of

her eldest daughters, Isabella Grace, Clementina, and Florence

Elizabeth, whom she would often dress up in costume tableau. The girls

were frequently shot - often in romantic and sensual poses - in pairs,

or, if alone, with a mirror or with their back to the camera. Hawarden's

photographic exploration of identity, otherness, the doppelgänger and

female sexuality, as expressed in the vast majority of these

photographs, was incredibly progressive when considered in relation to

her contemporaries, most notably Julia Margaret Cameron. As Graham

Ovenden comments in Clementina Lady Hawarden (1974), "Clementina

Hawarden struck out into areas and depicted moods unknown to the art

photographers of her age. Her vision of languidly tranquil ladies

carefully dressed and posed in a symbolist light is at opposite poles

from Mrs Cameron's images...her work...constitutes a unique document

within nineteenth-century photography."

She exhibited, and won silver medals, in the 1863 and 1864 exhibitions

of the Photographic Society, and was admired by both Oscar Rejlander,

and Lewis Carroll who acquired five images which went into the Gernsheim

Collection and are now in Texas. In 1865 Lady Hawarden died, and

although her loss was regretted in the photographic journals, her work

was soon forgotten.

More Information: http://www.artdaily.org/index.asp?int_sec=11&int_new=60585#.UYFHeEonlqN[/url]

Copyright © artdaily.org

More Information: http://www.artdaily.org/index.asp?int_sec=11&int_new=60585#.UYFHeEonlqN[/url]

Copyright © artdaily.org

Born Clementina

Elphinstone Fleeming in Dunbartonshire in 1822, she was the third of

five children of a British father, Admiral Charles Elphinstone Fleeming

(1774-1840), and a Spanish mother, Catalina Paulina Alessandro

(1800-1880). In 1845 she married Cornwallis Maude, an Officer in the

Life Guards. In 1856 Maude's father, Viscount Hawarden, died and his

title, and considerable wealth, passed to Cornwallis.

The surviving photographs suggest that Clementina, now Lady Hawarden,

began to take photographs on the Hawarden's Irish estate at Dundrum, Co.

Tipperary, from late 1857. Many of these were taken with a stereoscopic

camera, and the present collection contains several Dundrum images

which are one of the pair that comprise a stereoscopic image.

In 1859 the family also acquired a new London home at 5 Princes Gardens

(much of the square survives as built, but No. 5 has gone). From 1862

onwards Lady Hawarden used the entire first floor of the property as a

studio, within which she kept a few props, many of which have come to be

synonymous with her work: gossamer curtains, a Mark Haworth-Booth

offered Virginia Dodier the opportunity to make a freestanding mirror, a

small chest of drawers and the iconic 'empire star' wallpaper, as seen

in several of these photographs. The superior aspect of the studio can

also go some way to account for Hawarden's sophisticated, subtle and

pioneering use of natural light in her images.

It was also here that Lady Hawarden focused upon taking photographs of

her eldest daughters, Isabella Grace, Clementina, and Florence

Elizabeth, whom she would often dress up in costume tableau. The girls

were frequently shot - often in romantic and sensual poses - in pairs,

or, if alone, with a mirror or with their back to the camera. Hawarden's

photographic exploration of identity, otherness, the doppelgänger and

female sexuality, as expressed in the vast majority of these

photographs, was incredibly progressive when considered in relation to

her contemporaries, most notably Julia Margaret Cameron. As Graham

Ovenden comments in Clementina Lady Hawarden (1974), "Clementina

Hawarden struck out into areas and depicted moods unknown to the art

photographers of her age. Her vision of languidly tranquil ladies

carefully dressed and posed in a symbolist light is at opposite poles

from Mrs Cameron's images...her work...constitutes a unique document

within nineteenth-century photography."

She exhibited, and won silver medals, in the 1863 and 1864 exhibitions

of the Photographic Society, and was admired by both Oscar Rejlander,

and Lewis Carroll who acquired five images which went into the Gernsheim

Collection and are now in Texas. In 1865 Lady Hawarden died, and

although her loss was regretted in the photographic journals, her work

was soon forgotten.

More Information: http://www.artdaily.org/index.asp?int_sec=11&int_new=60585#.UYFHeEonlqN[/url]

Copyright © artdaily.org

More Information: http://www.artdaily.org/index.asp?int_sec=11&int_new=60585#.UYFHeEonlqN[/url]

Copyright © artdaily.org