![]() |

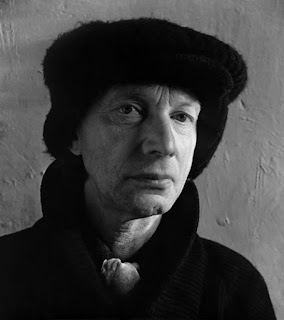

Self Portrait

|

“It is my deepest wish that photography; instead of falling in the domain of industry, or commerce, will be included among the arts. That is its sole, true place, and this is the direction that I shall always endeavor to guide it.” (1852)

Gustave Le Gray collection at The J. Paul Getty Museum

Gustave Le Gray portfolio at The Lee Gallery

Gustave Le Gray portfolio at Luminous-Lint

Gustave Le Gray portfolio at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gustave Le Gray seascapes at The Musée d'Orsay

![]() |

| "Boats Leaving the Port of Le Harve" |

![]() |

| "Giuseppe Garibaldi" |

![]() |

| "Empress Eugenie Praying" |

![]() |

| "Soldier and Camel" |

![]() |

| "Temple of Edfu" |

![]() |

| "Un Effectg de Soleil" |

![]() |

| "Zouave Story Teller" |

Gustave Le Gray Auction News from Art Info:

Gustave Le Gray Sails Away With a World Auction Record for Nineteenth-Century Photography

At Rouillac's photography auction in Vendôme, France, an image by Gustave Le Gray set a world record for a 19th-century photograph when it fetched €917,000 ($1,305,000), including the buyer's premium. After a fierce bidding war, a Houston oil magnate won the beautifully composed seascape, beating out one bidder from France and another from an unspecified oil-producing state.

Four prints exist of the image, "Bateaux Quittant le Port du Havre" ("Boats Leaving the Port of Le Havre") (see above), which dates from 1856 or 1857. It measures roughly 12 by 16 inches and is an albumen print (meaning that Le Gray used the albumen found in egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper).

The ten Le Gray photographs at the sale fetched a total of €1.6 million ($2.3 million). Their provenance is very unusual, as they have all continuously been in the possession of a single family, having been collected by one of Le Gray's contemporaries, Charles Denis Labrousse. Another work from 1857, "La Vague Brisée" ("The Broken Wave"), fetched €372,000 ($529,400) — briefly establishing a world record for a 19th-century photograph before "Bateaux Quittant le Port du Havre" outshone it by fetching over twice that sum. "La Vague Brisée" had a high estimate of only €120,000.

Gustave Le Gray Biography by Malcolm Daniel of the Department of Photographs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884) was the central figure in French photography of the 1850s—an artist of the first order, a teacher, and the author of several widely distributed instructional manuals. Born the only child of a haberdasher in 1820 in the outskirts of Paris, Le Gray studied painting in the studio of Paul Delaroche, and made his first daguerreotypes by at least 1847. His real contributions—artistically and technically—however, came in the realm of paper photography, in which he first experimented in 1848. The first of his four treatises, published in 1850, boldly—and correctly—asserted that "the entire future of photography is on paper." In that volume, Le Gray outlined a variation of William Henry Fox Talbot's process calling for the paper negatives to be waxed prior to sensitization, thereby yielding a crisper image.

By the time Le Gray was assigned a Mission Héliographique by the French government in 1851, he had already established his reputation with portraits, views of Fontainebleau Forest, and Paris scenes, as well as through his writing. Le Gray's mission took him to the southwest of France, beginning with the châteaux of the Loire Valley, continuing with churches on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela, and eventually to the medieval city of Carcassonne just prior to "restoration" of its thirteenth-century fortifications by Viollet-le-Duc. He traveled with Auguste Mestral, sometimes photographing sites on Mestral's Mission list, and at other times working in collaboration with him.

In the 1852 edition of his treatise, Le Gray wrote: "It is my deepest wish that photography, instead of falling within the domain of industry, of commerce, will be included among the arts. That is its sole, true place, and it is in that direction that I shall always endeavor to guide it. It is up to the men devoted to its advancement to set this idea firmly in their minds." To that end, he established a studio, gave instruction in photography (fifty of Le Gray's students are known, including major figures such as Charles Nègre, Henri Le Secq, Émile Pecarrere, Olympe Aguado, Nadar, Adrien Tournachon, and Maxime Du Camp), and provided printing services for negatives by other photographers.

Flush with success and armed with 100,000 francs capital from the marquis de Briges, he established "Gustave Le Gray et Cie" in the fall of 1855 and opened a lavishly furnished portrait studio at 35 boulevard des Capucines (a site that would later become the studio of Nadar and the location of the first Impressionist exhibition). L'Illustration, in April 1856, described the opulence intended to match the tastes and aspirations of Le Gray's clientele: "From the center of the foyer, whose walls are lined with Cordoba leather … rises a double staircase with spiral balusters, draped with red velvet and fringe, leading to the glassed-in studio and a chemistry laboratory. In the salon, lighted by a large bay window overlooking the boulevard, is a carved oak armoire in the Louis XIII style … Opposite over the mantelpiece, is a Louis-XIV-style mirror … [and] various ptgs arranged on the rich crimson velvet hanging that serves as backdrop … Lastly on a Venetian table of richly carved and gilded wood, in mingled confusion with Flemish plates of embossed copper and Chinese vases, are highly successful test proofs of the eminent personages who have passed before M. Le Gray's lens … However, the principal merit of the establishment is the incomparable skill of the artist …."

Despite a steady stream of wealthy clients, the construction and lavish furnishing of his studio ran up huge debts. Perhaps in an attempt to alleviate these financial problems, or perhaps because he enjoyed the artistic challenges of landscape more than the routine of studio portraiture, Le Gray produced some of his most popular and memorable works in 1856, 1857, and 1858—further views of Fontainebleau Forest (1987.1011; now with glass negatives and albumen silver prints), and a series of dramatic and poetic seascapes that brought international acclaim. Despite critical praise and apparent commercial success (one 1857 review cited 50,000 francs in orders for seascapes), Le Gray was, in truth, a better artist than businessman. Nadar wrote that by 1859, Le Gray's financial backers were "manifesting a degree of agitation and the early signs of fatigue at always paying out and never receiving"; they accused him of drawing more personal income than allowed under contract, paying no interest on his loans, and refusing to open his books for inspection. The portrait business was threatened, too, by the popularity of the new carte-de-visite, small, mass-produced portraits that were far cheaper to buy than Le Gray's grand productions. Again, Nadar writes that "Le Gray could not resign himself to turn his studio into a factory; he gave up." On February 1, 1860, Gustave Le Gray et Cie was dissolved.

At the age of forty, Le Gray closed his studio, abandoned his wife and children, and fled the country to escape his creditors. He joined Alexandre Dumas, setting sail from Marseille on May 9, 1860, "to see," in Dumas' words, "places famous in history and myth … the Greece of Homer, of Hesiod, of Aeschylus, and of Augustus; the Byzantium of the Latin Empire and the Constantinople of Mahomed; the Syria of Pompey, of Caesar, of Crassus; the Judea of Herod and of Christ; the Palestine of the Crusades; the Egypt of the Pharaohs, of Ptolemy, of Cleopatra, of Mahomed, of Bonaparte … to raise the dust of a few ancient civilizations." For Le Gray, the voyage provided both an escape and new subjects to photograph. En route to the East, Dumas detoured to aid Garibaldi in his Italian nationalist struggle by returning to Marseille to collect a boatload of arms. Le Gray photographed Garibaldi and the barricaded streets of Palermo. After being abandoned in Malta following a conflict with Dumas two months into the voyage, Le Gray eventually made his way to Lebanon and finally Egypt. There he spent the last twenty years of his life as a photographer and as a drawing tutor to the sons of the pasha. He never returned to France.